-Apuleius, THE GOLDEN ASS

A fundamental attribute to life and longevity, whether it be the life of a person or the life of a person's work, is that of maintaining motion. Switching, shifting, morphing, evading, transcending, joining, crossing over; these are all phrases which can describe the dynamic nature of experience, as old forms that become inhabitable are abandoned so that new forms may welcome the future. Man and his written work are synonymous in this way, primarily because they are an experience and the portrayal of that experience. Within the context of Menippean satire, this motion can be described as a kind of theft of perception, as it juxtaposes knowledge of slum naturalism and knowledge of the formal academy, banality and practicality and, most profound, philosophy and magic. The genre is a devious one, in that it is an agent of disorientation and chaos, questioning set structures by shaking their foundations so that they may be re-worked and re-presented. The theft, alteration, and re-presentation of perception is a process that philosophy and magic each deploy against one another in the Menippean satire in order to alter thinking; since the two schools operate with opposing methods, they are constantly interacting in the stories that have survived through the ages, and CONSOLATION OF PHILOSOPHY and THE GOLDEN ASS respectively illustrate this dynamic relationship between the two. With the aide of peripheral texts, these narratives bring this dynamic relationship to the forefront of their readings.

Interesting about the study of fiction, and what makes it a unique study, is that it is the exploration of the imaginary middle between concrete and imaginary. It confronts reality by making what is possible realizable, and then is able to maintain its guise of entertainment, or some other non-threatening form. It is what allows for the comparison between God and a woman in the songs “Jesus is All the World to Me” and “I’ve Got a Woman,” to become a heuristic model, showing that man is in constant need of company; fiction helps shape reality.

When reality, for example in the case of an empire, is a system that embodies the philosophical but disregards the magical or vice versa, it is works of fiction that will infiltrate this seemingly impenetrable system with ideas of an opposing school of thought, and open the system up to being influenced accordingly. Before addressing the aforementioned works, it is worthwhile to allow Plato's PHAEDRUS and Northrop Frye's ANATOMY OF CRITICISM to exemplify this relationship between philosophical and magical thought. Northrop Frye's ANATOMY OF CRITICISM states that, "The Menippean satire deals less with people as such than with mental attitudes... [it] presents people as mouthpieces of the ideas they represent" (Frye 309). This statement deconstructs the notion that stories have to be about people or things, which is how the Menippean satire "presents us with a vision of the world in terms of a single intellectual pattern" (310). In Frye's framework, the Menippean satire is not confined to having to describe place and character, but rather is obliged to portray the ideas that circulate within them. For example, Frye makes the point that, "Plato [...] is a strong influence on [colloquial narratives], which stretches in an unbroken tradition down through those urbane and leisurely conversations which define the ideal courtier in Castiglione or the doctrine and discipline of angling in Walton" (310). These colloquial works, though preceding the Menippean satire, would influence the style in which the genre would be written.

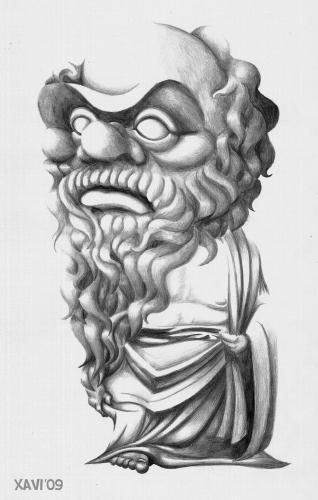

Socrates before the wrath of Eros.

Keeping objectivity (i.e., settings and characters) peripheral to the core ideas of the narrative allow the "mouthpieces" to let their ideas interact with one another with no confines other than those manifested by opposing rhetoric. In Plato's PHAEDRUS, Socrates and Phaedrus walk outside the city limits to have a conversation on love and rhetoric, and Socrates' rationality leads him to conclude that love is negative and undesirable. His philosophy thus becomes too bold for his own good, because it is blasphemous to the god of love, Eros. Socrates must then refute his philosophy by means of its opposite, magic, in this case via poetry:

Soc. Ere any evil befall me for my defamation of Love, I will offer [Eros] my palinode by way of atonement, with my head bare, and no longer, as before, muffled up for shame.

Pha. You could not have said anything that would give me greater pleasure than this.

Soc. I believe you, my good friend; for you feel as well as I do, how shameless was the tone of both our speeches... Out of delicacy then to such a lover as this, and for the fear of the god of love himself, I desire by a fresh and sweet discourse to wash out, so to speak, the brackish taste of the stuff we have just heard (Plato 41-42).

It is clear in this above example that Socrates' philosophy has gone too far, and taken the offensive against the magical. It is also clear that he realizes that he needs to appeal to magic in order to keep himself a balanced thinker, and avoid slipping into becoming a philosophus gloriosus and cursed by Eros; this dual is one of prose versus verse. Prose indicates the analytical flow of rational thinking, whereas verse indicates the emotional, the spontaneous and the magical.

Lady Philosophy; notice how she is confronting "poetry," as her vision appears glazed and unwilling to accept its request to enter the man that she has come to protect.

In CONSOLATION OFO PHILOSOPHY, Boethius is in a situation that is opposite that of Socrates in PHAEDRUS, but similar in nature. The situation is captured by this same prose/verse dichotomy of philosophy and magic in fiction. Here, a poet, existentially shaky as he nears his death and the disappearance of his creativity, expresses himself through verse. He asks the nine Muses to console him by giving him a burst of creativity before he dies. He appeals to magic in order to articulate his emotionality, in hopes of "dictating words to [his] tears" (Boethius 3). This is blasphemous to philosophy. Disgusted, philosophy takes the form of a woman and appears in Boethius' bedroom, blasting the weak man for allowing himself to give in to the "poisons" of poetry.

In the midst of what begins as a poetic project, Philosophy makes its appearance and disrupts the artistic process of the author. Like Socrates in PHAEDRUS, Boethius loses his balance of mind and is at the mercy of the opposing side: philosophy. Like a mother, Philosophy shows her annoyance at how her son could stray to easily from rationality to become the victim of despair and self-centered art:

Are you really the same man who, once upon a time, nursed with my milk, raised on my food, emerged into the strength and vigor of a mature mind? Yet we had supplied you with such weapons as would still be protecting you now, unconquered and unshakable, if you hadn't cast them away beforehand (5).

"Weapons" are metonymous for practical ideas, as the narrator has obviously become lethargic in his thinking towards the end of his life; he has submitted to his decay because he is lazy, but tries to legitimize his lifestyle by being creative with it. This does not fool Philosophy in the least, who sees the narrator's self-defense as mere "complaining," and she is able to recognize his blasphemy against her in the way that he compares the earth to the heavens. In the same way that Socrates the mortal unintentionally puffs himself up to rival Eros the God, so Boethius' thoughtlessness as a pathetic wish-maker contradicts the logic of Philosophy the Almighty Thinker. This is exemplified when Philosophy states that,

... ultimately it was your lamentation against Fortune that glowed white-hot; you complained, in the last lines of your delirious Muse, that rewards are not paid out that are equal to merits, and you made a wish that the peace that rules the heavens rule the earth as well (17).

At work then in CONSOLATION OF PHILOSOPHY is the theft of magical perception by philosophical perception, and its re-working in such a way as to cast out poetic masochism so that reason may point the narrator's creativity in a direction that does not disregard rationality via poetic lament, but rather co-exists with its practicality. The "direction" is synonymous with the narrator's trajectory toward death, referred to in the narrative as "Fortune." Fortune is that which philosophy and magic each fight for the right to portray, just as it was "Love" in PHAEDRUS. Magic is trying to turn Fortune into something that is, in the end, undesirable: it brings with it the inevitability of death, and embodies lost energy and creativity that age eventually steals away. If embodied by a poem, at least this nasty Fortune might be captured to warn others of the reality of old age, or at least be a sedative to the suffering poet. The role of the magical in this narrative is that of an opiate, to numb those experiencing old age. Boethius does not intend for his readers to regard magic as a good thing in this way, but to realize what it is about magic that might be appealing to someone in the narrator's position; the narrator is allowed to grieve for the life that he hasn't lost yet, but is preparing to lose. This is made clear when he writes that, "While faithless Fortune was partial to me with ephemeral favors / A single, deplorable hour nearly plunged me in my grave" (2). Magic is the poet’s escape ability, that which allows his thought to assume the third-person perspective so that his dying body may be released from the torments of actuality.

Just as Socrates is able in PHAEDRUS to remain philosophical while also address magic in its native language of poetry, so to is lady Philosophy. Her verse speaks to the sentimentality of the narrator, but instead of appealing to his emotional squalor, she addresses his depleting life within the context of the larger world around him:

No, there is more -- every cause: why in their bluster

Stormwinds can tease and excite ocean's calm surface;

What spirit rotates the earth, stable, unmoving;

How can the stars that will fall in the Atlantic

Rise up again in the East, radiant-dawning;

What renders tranquil and calm the hours of the spring day,

So to adorn all the earth with rose-colored flowers;

Who was the reason that Fall in the year's fullness,

Fertile and rich, overflows, grapes full to bursting... (4).

Frye sees CONSOLATION OF PHILOSOPHY as an analytical piece rather than as simply a provocative piece of fiction, because "...its verse interludes and its pervading tone of contemplative irony is a pure anatomy, a fact of considerable importance for the understanding of its vast influence" (Frye 312). What Boethius is analyzing is not a literal woman named "Philosophy" and a literal narrator named "Old Poet" who have a conversation about something called "Fortune." Boethius is, by means of making man into mouthpiece, exploring the human mind and how it is an object that is subject to opposing modes of being: philosophical and magical. That the narrator is malleable in his thinking, able on the one hand to anesthetize himself with the magic of emotionality, and on the other, to place himself in the "true light" with philosophy, affirms the idea that the Menippean satire articulates a "single intellectual pattern." Boethius, a Christian during his life, may be guiding this intellectual pattern by making lady Philosophy's "axioms of books" and "the light" synonymous with God. God's existence is therefore something that is reasonable, a logical place of sanctuary to one whose life is about to expire.

However, if Fortune to Lady Philosophy is the path of reason that which will eventually guide one out of life and into light, Socrates, down and out wearing rags, is made the victim of it in THE GOLDEN ASS. Apuleius punks Lady Philosophy’s conception of Fortune, as Socrates so desperately says, "Leave me be! Leave me be! I am the monument that Fortune has made -- let her enjoy the sight of it in triumph while she can" (Apuleius 7); this is Socrates' submission to the light, which turns out to be a trap. His downfall in THE GOLDEN ASS is similar to his downfall noted by Lady Philosophy in CONSOLATION OF PHILOSOPHY, when she stood by his side and watched him “[win] the victory of an unjust death” (Boethius 7), because it signifies a significant blow to logic; his death, in both of these works, marks the end of pure philosophical thought. From his downfall on, one can expect irrationality and emotion to take over. In CONSOLATION OF PHILOSOPHY, for example, the Epicurians and Stoics drag a tattered Philosophy off with them after Socrates passes; in THE GOLDEN ASS, Socrates' death signifies the beginning of the narrator’s descent into the mystical situations of the narrative, eschewing the greater narrative from rationality. If Socrates is to represent philosophy itself, then Apuleius is refuting Boethius' construct of philosophy as dominating magic, and this is apparent in the way that he kills Socrates, who immodestly "wolfs" his food and "greedily" reaches for drink (Apuleius 16-17), to open the story to the influence of magic. The story of Socrates' death leaves the theme of Fortune dangling and up-for-grabs to both philosophy and magic; as THE GOLDEN ASS unfolds, Fortune indeed falls into the hands of magic.

Emotions take control of the telling of THE GOLDEN ASS: magic meets philosophy, and magic wins. This episode in the story is a prolepsis for the increasing abandonment of logic and rationality, and it is the woman that is the mouthpiece for magic itself. She symbolizes the mysteriousness of birth and the hypnotizing manipulation that magic is capable of, if we recall Meroe's sinister reputation for witchcraft, Venus' wrathful vanity, and Isis' natural and awesome majesty. Though the story of philosophy's death is interpolated into the larger narrative, it is especially central in the interaction between philosophy and magic in the novel, because of its explicitness: magic kills philosophy.

What does magic prove by shutting philosophy out of this narrative? It blasts the institutionally trained intellectual by subliminally offending him: it changes him into an ass, which would seem an explicit insult, until it is apparent that the form of an ass may be a beneficial one for the academic who is completely ignorant of the slum-naturalistic knowledge that circulates outside of the academy’s walls. It allows him to hear better because of having bigger ears, and while other people assume him to be dumb, they say anything in front of him. Magic is casting a spell in a sylleptic way, in that it stuns the reason of the formally trained thinker by cursing him to a beastly form on the one hand, but also endowing him with certain faculties which increase his capacity for learning more on the other. Thus, the magical proves that there is another side to reality that philosophy shuts out, and it is understood by the upper and lower tiers of the three-tiered geographical model of setting, Heaven and Hell, where Earth is merely the space of ambivalence and superfluous rhetoric in between. It is only with magical communication then, as in PHAEDRUS, that the Gods are able to interact with mortals and bridge the three-tiered model; philosophy helps mortals on earth, but gets them into trouble when it reaches the Gods, as it gets lofty and challenges magic. On these grounds, magic transcends philosophy in the realm of the unexplainable.

THE GOLDEN ASS and CONSOLATION OF PHILOSOPHY each set forth their central ideas with the monolithic figure of a woman; magic's deployment of woman in the form of Isis is resonant with its mysteriousness and hypnotic nature, while philosophy's deployment of woman resounds with its groundation in the real, symbolized by “breast feeding” (Boethius 5). Lady Philosophy is nurturing throughout a man's life, and she will arrive when her sons and daughters neglect her teachings:

Are you really the same man who, once upon a time, nursed with my milk, raised on my food, emerged into the strength and vigor of a mature mind? ... He has forgotten himself for a time, but he'll remember easily enough, since he knew us once before (5).

Lady Philosophy is to be followed with logic in this case, whereas Isis operates in a different way; she is to be followed with trust. She arrives when called upon out of mercy, and though she is the "mother of the universe," she only gives birth, and then nurtures when her children are merciful, and realize that they need her. Lucius pleads to her, "return me now to the sight of those who love me, return me now to the Lucius I used to be" (Apuleius 234). Isis answers his plea, and first calls attention to her majesty and divinity before even addressing Lucius, saying "... I have been moved, and here I am -- I, the mother of the universe..." (235). Lady Philosophy's first words, on the other hand, address the issue at hand right away, as she uses no introductory words to convey her power, but rather gets right to the point: "Who let these little stage whores come visit this invalid" (Boethius 3)? Isis thus grants man salvation when he goes to her, and Lady Philosophy when he least expects it. Magic is a practice that will effect those, like Lucius, that wander into it, and philosophy one that will reel in the mystical when it pulls a person in, as with the old poet in CONSOLATION OF PHILOSOPHY.

That Lucius' final metamorphosis is that into holy man is interesting, because he gives into magic with full commitment, consistent with his intentions of discovering it at the beginning of the story; he goes to it with full intent on understanding it, the ultimate gouge against philosophy being the idea that not everything can be explained with logic and education. This reading would imply that Apuleius is celebrating the personal leap into religious cultism, falling in line with Merkelbach's thesis that this novel's main function is to legitimize Isis worship.

The assessment of philosophy and magic’s battle in these works points back to Plato’s Phaedrus. After Socrates repents to Eros, he begins a new and fresh discourse so as not to anger the gods. It is one that is about poetry and madness, and how madness is to be seen in positive light as long as it comes to a person from the gods. This leads him to the question, "What is a soul?" His modeling of his answer is applicable in examining the philosophy in CONSOLATION OF PHILOSOPHY and magic in THE GOLDEN ASS, and their relations; it is a dualistic model, but in orbit around a common theme, as in the case of Fortune:

First of all then I must investigate the truth with regard to the nature of the soul, both human and divine, by observing its conditions and powers... Every soul is immortal -- for whatever is in perpetual motion is immortal. Now the thing which moves another and is by another moved [...] may cease also to live; it is only that which moves itself, inasmuch as it never quits itself, that never ceases moving, but is to everything else that is moved a source and beginning of motion (Plato 45-46).

Philosophical reason and magical trust are thus the souls in which the Menippean satire provides the motion, allowing Lady Philosophy and Isis to be colloquially connected in a conversation will most likely never end.

What makes the interaction between philosophy and magic in the Menippean satire worth investigating is its resonance with other interactions between opposing forces in the social sciences. A good example is that between the political and the cultural. While the former operates under the pretenses of philosophy and law, the latter operates with a more devious and anachronistic mysticism. As noted earlier, when a system embodies one of these modes and becomes impenetrable, it covers one of reality's eyes and becomes exclusive and favoritistic with that which it strives to convey. CONSOLATION OF PHILOSOPHY and THE GOLDEN ASS, as representations of each type of system, are useful and fruitful in assessing such relationships as "political versus cultural." By de-legitimizing its opposition, re-assessing the conflicting issues at hand, and then re-presenting a solution to the reader, THE GOLDEN ASS and CONSOLATION OF PHILOSOPHY each model Frye's contention that the Menippean satire strives to present a reality that abides by a single intellectual pattern.

A classic photograph of political/cultural confrontation during an exceptionally split time.

===============================================

- Apuleius. The Golden Ass. Trans. Joel C. Relihan. Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Co., 2007.

- Boethius. Consolation of Philosophy. Trans. Joel C. Relihan. Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Co., 2001.

- Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism. Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Plato. The Phaedrus, Lysis, and Protagoras of Plato. Trans. J. Wright. New York: MacMillan Company, 1900.

No comments:

Post a Comment